From foundation to footnote: how grains lost their place in the food pyramid

8 January 2026

For decades, grains sat at the base of the food pyramid – literally and figuratively.

They were framed as the foundation of a healthy diet, the food group to be eaten most often and in the greatest quantity. Protein was moderated. Fat was restricted. Animal foods were treated with suspicion. This hierarchy didn’t just shape personal diets; it shaped agricultural subsidies, school lunches, hospital food, food manufacturing, and public perception of what “healthy eating” looked like.

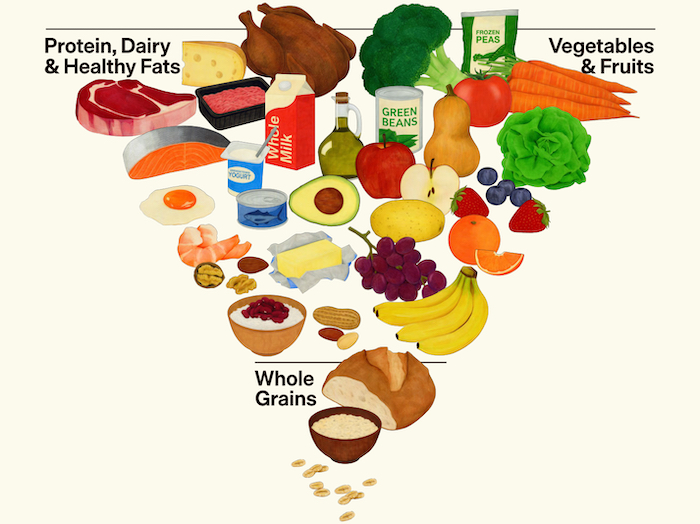

The newly released Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025–2030 dismantle that hierarchy.

There is no reckoning with the past. No admission of error. But structurally, unmistakably, the pyramid has been inverted.

Protein now comes first.

Full-fat dairy is restored.

Healthy fats are explicitly included.

And grains – once the unquestioned foundation – now appear last.

This shift matters far beyond nutrition advice. It signals what may be a slow, cautious retreat from a food system built on carbohydrate primacy.

The old pyramid wasn’t neutral

The original grain-heavy pyramid was never just a visual guide. It was a policy instrument.

Positioning grains as the dietary base justified:

- Large-scale grain subsidies

- Expansion of refined grain products marketed as “healthy”

- Low-fat, high-carbohydrate dietary guidance

- The marginalisation of animal foods in public health messaging

Once embedded, that framework became self-reinforcing. Industry aligned with policy. Policy aligned with guidelines. Guidelines shaped public belief. By the time health outcomes deteriorated, the system was too large – and too profitable – to question easily.

As ultra-processed foods multiplied, they did so largely on a grain base. Bread, cereal, pasta, crackers, snack bars, and fortified flours became vehicles for overconsumption, additives, and claims of health – all while being defended by their position at the base of the pyramid.

What changed in the 2025–2030 guidelines

The most striking feature of the new guidelines isn’t what they remove – it’s how they reorder priorities.

Protein is no longer a side consideration. It is explicitly prioritised at every meal, with intake targets far higher than in previous guidance. Animal-sourced protein is named repeatedly, not hedged or apologised for.

Dairy reappears without the decades-long caveat of “low-fat only”. Full-fat dairy is recognised for its role in delivering protein, fats, and micronutrients – something many populations never stopped consuming despite official advice.

Fats are no longer framed as something to be minimised. Butter and beef tallow are included as healthy options, signalling a departure from blanket fat avoidance.

Vegetables and fruits are encouraged in whole form, with repeated warnings against highly processed foods – a notable shift from earlier guidelines that often treated processing as secondary.

And then, finally, come grains – after protein, dairy, healthy fats, vegetables, and fruits.

Not as a foundation.

Not as essential.

But limited in quantity, restricted in quality, and framed with caution.

“Prioritise fibre-rich whole grains.”

“Significantly reduce refined carbohydrates.”

“2–4 servings per day“ – a far cry from the 6–11 daily servings promoted under the original grain-first food pyramid – a framework that continued through later models such as MyPyramid and MyPlate, and still shapes public understanding of “healthy eating“ today.

Grains are no longer framed as central, but as something to be limited and managed.

A reversal without a reckoning

What’s notable is how carefully this change is handled.

There is no acknowledgment that the grain-first model coincided with rising obesity, diabetes, and metabolic disease. There is no reflection on how decades of guidance shaped the modern food environment. The shift occurs without apology or accountability.

Instead, the document speaks of “real food”, “nutrient density”, and “returning to basics” – a rhetorical reset that allows policy to move forward without explicitly confronting its past.

From a systems perspective, this makes sense. A full reckoning would implicate not only dietary advice, but agricultural priorities, corporate food interests, and public institutions built around the old model.

The hierarchy has changed.

The narrative has not. Yet.

How change actually happens

This pattern of slow, careful change is not new.

In 2015, a comprehensive scientific review published in Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism examined large population studies across Japan, Europe, and elderly cohorts worldwide. It found that higher total and LDL cholesterol levels were consistently associated with lower all-cause mortality in older populations, while low cholesterol was often linked to higher risks from cancer, infection, and stroke.

The authors state:

Survival rate is definitely better in elderly people with high total or LDL cholesterol levels than in those with low levels.

That same year, the US Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee concluded:

Cholesterol is not a nutrient of concern for overconsumption.

Yet the official dietary guidelines softened the message, public advice barely changed, and clinical practice has lagged behind the evidence for years.

The lesson was not about cholesterol. It was about systems.

Nutrition policy rarely shifts all at once. Evidence moves first. Advisory language follows cautiously. Public guidance lags further still. Cultural habits are slowest of all to change.

What this means for the food system

Moving grains from foundation to periphery destabilises long-standing assumptions.

If grains are no longer the base:

- What would justify their continued dominance in school meals?

- Will food assistance programmes continue to rely heavily on refined carbohydrates?

- Will ultra-processed grain products still be framed as dietary staples?

- And will small-scale meat producers still be treated as environmentally or nutritionally suspect?

This shift also aligns, perhaps unintentionally, with what many traditional food cultures never abandoned: diets built around animal foods, dairy, fats, and seasonal plants – with grains as a supplement, not a cornerstone.

For farmers, ranchers, fishers, and small producers focused on nutrient-dense foods, this represents a subtle but meaningful validation. Not yet a win. Not yet a reversal of policy. But a crack in the narrative.

The pyramid didn’t fall – it flipped

That matters, because while the hierarchy changed abruptly, food systems do not.

They shift slowly, constrained by infrastructure, economics, and political caution. The 2025–2030 guidelines reflect a system beginning to acknowledge its limits – and backing away from its most confident claims.

Grains are no longer the foundation.

They are no longer framed as essential.

They are no longer positioned as the primary driver of health.

Instead, they are constrained – limited in quantity, conditional in quality, and clearly secondary to protein, healthy fats, dairy, vegetables, and fruits.

And in food system terms, that is a profound change.